UFOS AND GOVERNMENT amazon.com/UFOs-Government-Historical-Michael-Swords |

|

|

In the latter part of 1957, due to the

International Geophysical Year and the

launchings of the Soviet satellites, a program

was initiated that drove many people outdoors,

looking at the sky. The program was called

Operation Moonwatch. Moonwatch was mainly composed of amateurs under the supervision of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), directed by Harvard meteor expert, Dr. Fred Whipple, and assisted by J. Allen Hynek. Moonwatch's goal was the accurate plotting of Soviet and U.S. satellite orbits.48 The program was supported by some excellently-designed tracking telescopes, the "Baker-Nunn" cameras. People were excited about the human race breaking into space, and many persons volunteered. As far as UFOs were concerned, this project

put many trained and semi-trained observers into

place to scan the heavens. From most viewpoints

this was a good thing, but not necessarily to

the Air Force.They did not want more UFO stories

coming in from a government program. In

practice, things should have been fairly well

controlled. Project Director Whipple was Donald

Menzel’s closest friend on the Harvard Astronomy

Staff and a consultant to Blue Book. What could

be a better-controlled situation? As it turned

out, the situation could have been much better

for the Air Force. Citizens talked, and Allen

Hynek began to let his curiosity get the better

of himself. Hynek began to think that, at a

minimum, there were things in the UFO

observations that pointed to at least one new

natural phenomenon, if not several. Whereas some

higher personnel in the SAO Moonwatch

organization did not want citizen observers to

log “unidentifieds” even if they obviously were

not satellites, Hynek wanted the cases and

he was not alone.49 One of his assistants,

Bud Ledwith, was very interested; so was a young

apprentice named Walter Webb. Both went on to do

research on UFOs beyond Moonwatch, and Webb made

a lifetime of it. So signals to the citizen

observers were mixed. Many logs of unidentified

“non-satellites” were received. Doubtless more

were never logged. Hynek gathered additional

information by “personal communication.” But

these observations were generally kept very

quiet. Only in later years would anybody outside

the SAO, Hynek, Webb, et al., have any inkling

of the numbers. It is a story still untold. But

we will tell a little of that story in the next

chapter. Suffice it to say for now that in those

times the science media used Moonwatch as an

argument against UFOs: with so many trained

observers looking, surely Moonwatch would have

seen unidentified objects if there were any;

and, of course, they have not.50 It was just one

more peculiar untruth in what seems to be an

endless continuous stream of disinformation.

Sputnik went up in early October and so did

UFO reports. Some commentators say that those

reports were Soviet hysteria; some say it was

just because people were outside looking for

Sputnik. In October, reports were about twice

what the earlier months averaged, but when the

1957 flap occurred in early November, the cases

shot up to ten times the earlier rate.51 The

flap is much too dense and powerful to describe

thoroughly in a few pages here. Instead, our

coverage of the flap will concentrate upon two

main topics: how the phenomenon, for the first

time in the United States, “came closer,”

manifesting itself with “close encounters”

involving physical effects on both technology

and people; and how the government dealt with

these issues to keep the country from becoming

too excited or frightened.

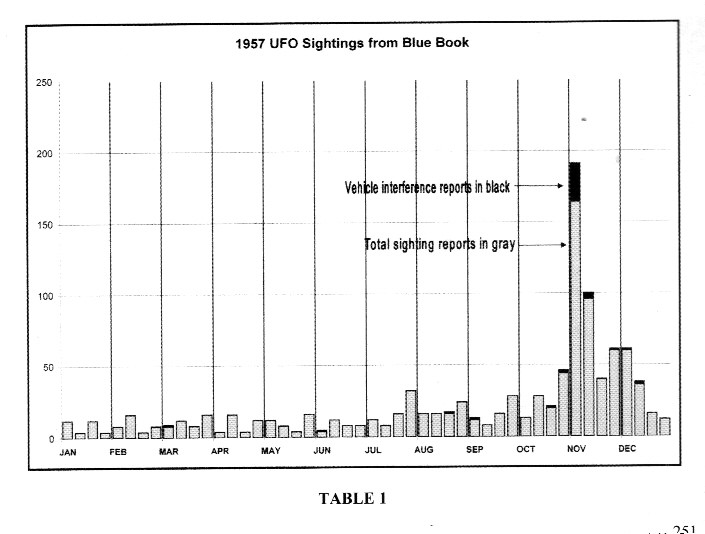

Table 1 shows what the Air Force had to deal with

as the number of cases exploded.52 It represents

what UFOlogists would call a concentrated national

“flap.” The year 1957 was proceeding fairly

quietly until the very end of October. Then case

reports rocketed off the chart, spiking on the 5th

and 6th of November. The rate of incidents was far

beyond the capability of the Air Force to properly

investigate. And this flap was distinctively

different. Hidden within the sheath of

old-fashioned UFO reports was the sharp blade of a

new (for the United States) phenomenology: close

encounters. These close encounters mainly bore a

distinct characteristic: the failures of

automobile engines (and often other devices, such

as lights and radios) that were coincident with

the presence of an unidentified object, and felt

by the witness to be due to that object. Also

embedded in the flap, in lesser, but still

interesting, amounts, were several cases in which

the witnesses seemed to have received a mild

“burn” from the light, heat, or other radiation

from the offending object. Both of these

UFO-related or UFO coincident phenomena were very

rare in previous American records. Both of these

were much more personal and potentially

threatening than what military and civilians had

typically dealt with before. How would the

citizenry react? How would the military?   All of this is part of the mystery: each era

is partly distinctive, partly the same. The

sameness would lead students towards linking the

phenomenology, the differences to tearing the

phenomenology apart. It was always this latter

elementthat the phenomenon would not present a

tight, predictable patternthat had been the

strongest Air Force tool for arguing against it,

and the argument that was featured in Blue Book

14. But sometimes intensity will overcome

everything else, and this was an intense flap

with spectacular aspects. How would it play out?

Earlier in the year (August 22, near Cecil

Naval Air Station, Florida),54 Blue Book had

become aware of an isolated case of a vehicle

stoppage and had written it off as the sighting

of a helicopter (ignoring the car engine

problem). Earlier still, several

radar-interference cases caused some to think

that UFOs could generate electromagnetic

radiation, perhaps even as directional pulses.55

Of course, no one was yet thinking about UFO

electromagnetic pulses stopping automobile

engines, but, as time went on, UFO researchers

would wonder about this and government labs

(such as Los Alamos and Sandia) would initiate

research programs on such things as a non-lethal

battlefield tool.56 All of this gained a feeling

of concrete reality in Western Texas on the

night of November 2 and 3.

|