|

The Nike Missile System A Concise Historical Overview

By Donald E. Bender

Updated 16 July 1999

Origins Of The Nike System

Nike, named for the mythical Greek goddess of victory, was

the name given to a program which ultimately produced the world's first

successful, widely-deployed, guided surface-to-air missile system.

Planning for Nike was begun during the last months of the Second World

War when the U.S. Army realized that conventional anti-aircraft

artillery would not be able to provide an adequate defense against the

fast, high-flying and maneuverable jet aircraft which were being

introduced into service, particularly by the Germans.

During 1945, Bell Telephone Laboratories produced the "AAGM

(Anti Aircraft Guided Missile) Report" in which the concept of the Nike

system were first outlined. The Report envisioned a two-stage,

supersonic missile which could be guided to its target by means of

ground-based radar and computer systems. This type of system is known

as a "command" guidance system. The main advantage over conventional

anti-aircraft artillery was that the Nike missile could be continuously

guided to intercept an aircraft, in spite of any evasive actions taken

by its pilot. By contrast, the projectiles fired by conventional

anti-aircraft artillery (such as 90mm and 120mm guns) followed a

predetermined, ballistic trajectory which could not be altered after

firing.

The Nike Mission

During the first decade of the Cold War, the Soviet Union

began to develop a series of long-range bomber aircraft, capable of

reaching targets within the continental United States. The potential

threat posed by such aircraft became much more serious when, in 1949,

the Russians exploded their first atomic bomb.

The perception that the Soviet Union might be capable of

constructing a sizable fleet of long-range, nuclear-armed bomber

aircraft capable of reaching the continental United States provided

motivation to rapidly develop and deploy the Nike system to defend

major U.S. population centers and other vital targets. The outbreak of

hostilities in Korea, provided a further impetus to this deployment.

The mission of Nike within the continental U.S. was to act

as a "last ditch" line of air defense for selected areas. The Nike

system would have been utilized in the event that the Air Force's

long-range fighter-interceptor aircraft had failed to destroy any

attacking bombers at a greater distance from their intended targets.

Nike Deployment

Within the continental United States, Nike missile sites

were constructed in defensive "rings" surrounding major urban and

industrial areas. Additional Nike sites protected key Strategic Air

Command bases and other sensitive installations, such as the nuclear

facilities at Hanford, Washington. Sites were located on

government-owned property where this was available (for example, on

military bases). However, much real estate needed to be acquired in

order to construct sufficient bases to provide an adequate defense.

This was a sometimes difficult and contentious process. Often, the

federal government had to go to court in order to obtain the property

needed for such sites.

The exact number of Nike sites constructed within a

particular "defense area" varied depending upon many factors. The New

York Defense Area -- one of the largest in the nation -- was defended

at one time by nearly twenty individual Nike installations. Due to the

relatively short range of the original Nike missile, the Nike "Ajax",

many bases were located relatively close to the center of the areas

they protected. Frequently, they were located within heavily populated

areas.

Nike Ajax missiles first became operational at Fort Meade,

Maryland, during December, 1953. Dozens of Nike sites were subsequently

constructed at locations all across the continental United States

during the mid fifties and early sixties. Roughly 250 sites were

constructed during this period. Nike missiles were also deployed

overseas with U.S. forces in Europe and Asia, by the armed forces of

many NATO nations (Germany, France, Denmark, Italy, Belgium, Norway,

the Netherlands, Greece and Turkey), and by U.S. allies in Asia (Japan,

South Korea, and Taiwan).

A "Typical" Nike Site

A "typical" Nike air defense site consisted of two separate

parcels of land. One area was known as the Integrated Fire Control

(IFC) Area. This site contained the Nike system's ground-based radar

and computer systems designed to detect and track hostile aircraft, and

to guide the missiles to their targets.

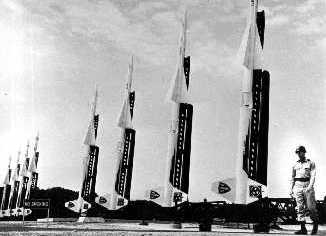

The second parcel of land was known as the Launcher Area. At

the launcher area, Nike missiles were stored horizontally within

heavily constructed underground missile "magazines". A large, missile

elevator brought the Nikes to the surface of the site where they would

be pushed (manually) by crewmen, across twin steel rails to one of four

satellite launchers. The missile was then attached to its launcher and

erected to a near-vertical position for firing. The near-vertical

firing position ensured that the missile's booster rocket (lower stage)

would not crash directly back onto the missile site, but, instead,

would land within a predetermined "booster impact area".

The control and launcher areas were separated by a distance

of 1,000 to 6,000 yards (roughly 0.5- to 3.5-miles) and were often

located within different townships. Technical limitations of the

guidance system required the two facilities to be separated by a

minimum of 3,000 feet. Whenever possible, control areas were

constructed on high ground in order to gain superior radar coverage of

the area. Control areas were generally located between the area being

defended and the launcher area containing the missiles.

Nike "Ajax": The First Nike Missile

The first successful test firing of a Nike missile occurred

during 1951. This first Nike missile was later given the name Nike

"Ajax". Nike Ajax was a slender, two-stage guided missile powered by a

liquid-fueled motor utilizing a combination of inhibited red fuming

nitric acid (IRFNA), unsymmetrical dimethyl hydrazine (UDMH) and JP-4

jet petroleum. The Ajax was blasted off of its launcher by means of a

jettisonable solid fuel rocket booster which fired for about 3 seconds,

accelerating the missile with a power of 25 times the force of gravity.

The Ajax missile was capable of maximum speeds of over

1,600-mph and could reach targets at altitudes of up to 70,000 feet.

Its range was only about 25 miles, which was too short to make it a

truly effective air defense weapon in the eyes of its many detractors.

Its supporters countered that the new missile was markedly superior to

conventional antiaircraft artillery, and that it was, significantly,

the only air defense missile actually deployed and operational at that

time.

Nike Ajax was armed with three individual high-explosive,

fragmentation-type warheads located at the front, center and rear of

the missile body. Although consideration was given to arming the Ajax

with a nuclear (atomic) warhead, this project was canceled in favor of

developing a totally new, much-improved Nike missile. Even as the first

Nike Ajax missiles were being deployed across the nation, work on its

successor, first known as "Nike-B" and later as Nike "Hercules" had

already begun.

The Nike "Hercules" Missile

Work on a successor to the first Nike missile, the Nike

"Ajax", was initiated well before the first Ajax missiles were deployed

at sites across the nation. Two primary considerations drove the

development of the this second-generation Nike missile. The first

involved the need to field a missile with improved capabilities to

defend against a new generation of faster and smaller targets,

including supersonic aircraft and tactical ballistic missiles. The

second was the desire to arm this new missile with a powerful atomic

warhead.

Originally designated as "Nike B", the Nike "Hercules" -- as

this missile was later known -- was a far more capable missile than its

predecessor (the Nike Ajax) in nearly every way. With a maximum range

of about 90 miles, maximum speeds of over 3,200 mph, and the ability to

reach targets at altitudes in excess of 100,000 feet, the Nike Hercules

was a very potent air defense weapon. The Hercules missile lacked most

of the complex, miniaturized vacuum tubes utilized by the Ajax, and

employed solid rocket fuel in its "sustainer" motor which made it

easier and safer to manage than the Ajax which employed highly caustic

liquid fuel components.

Unlike the Ajax, the Hercules was designed from the outset

to carry a nuclear warhead. Designated "W-31" the Hercules nuclear

warhead was available in three different yields: low (3-Kilotons);

medium (20-Kt.) and high (30-Kt.). For purposes of comparison, the

atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, near the end of the Second

World War had a yield of approximately 15 Kilotons.

Armed with its nuclear warhead a single Nike Hercules

missile was capable of destroying a closely spaced formation of several

attacking aircraft. This warhead enabled the Hercules to destroy not

only the aircraft, but also any nuclear weapons they carried,

preventing them from being detonated. Some of the first Hercules

missiles deployed in the United States were initially equipped with the

heavier "W-7" nuclear warhead.

The Hercules could also be equipped with a powerful,

high-explosive, fragmentation-type warhead designated "T-45". The

warhead provided a useful alternative to the W-31 (particularly for use

against a single aircraft and for low altitude use in proximity to

populated areas) and was deployed at many overseas sites. Additional

warhead designs, including "cluster" type warheads containing numerous

submunitions, were developed although not deployed operationally on the

Nike Hercules missile.

More sophisticated radar and guidance systems were also part

of the Hercules "package". These made the Hercules system more accurate

and effective at longer ranges. During the early sixties, an "improved"

version of the Hercules system, utilizing ABAR (Alternate Battery

Acquisition Radar) or HIPAR (High Power Acquisition Radar) was

deployed. The improved radar capabilities and other advanced electronic

features of the Improved Hercules system made it more effective against

small supersonic targets including aircraft, aircraft launched

"stand-off" missiles, and tactical ballistic missiles.

An relatively unknown fact is that the Hercules missile

could also be used in a surface-to-surface mode. In this role, the

Hercules would have been used to deliver tactical nuclear warheads to

destroy concentrations of enemy troops and armored vehicles, or

bridges, dams and other significant targets from bases and field

deployments located primarily within Western Europe. This surface

capability might also have proven useful in other areas where the

Hercules missile was deployed including South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey.

Maximum range of the Hercules missile in the

surface-to-surface mode was slightly over 110 miles, and was limited by

the effective transmission range of the Missile Tracking Radar (MTR).

Although deployed at permanent sites within the continental

United States, and at many overseas locations, mobile Nike Hercules

batteries increased the flexibility and usefulness of this system,

permitting the powerful capabilities of this versatile missile system

to be extended wherever this could prove useful. Trucks and trailers

were used to transport Nike Hercules system components to the desired

field locations. In this mode, a single missile was mounted upon a

truck-drawn trailer/launcher unit which also served as a firing

platform.

Guidance & Control

Unlike some modern missile systems, Nike was guided entirely

from the ground, from firing to warhead detonation. The electronic

"eyes" (radar) and "brain" (computer) of the Nike system were located

on the ground, within the Integrated Fire Control Area.

At the IFC area, hostile aircraft were first identified by

means of an acquisition radar (ACQR). This radar was manned 24 hours

per day, scanning the skies for indications of any hostile aircraft.

"Friendly" aircraft were automatically identified by means of

electronic signals generated by IFF ("Identification Friend or Foe") or

SIF ("Selective Identification Feature") equipment.

In practice, this target information would normally have

been received from Air Force long range radar sites, by means of the

Air Force's SAGE (Semi Automatic Ground Environment) system and other

sources including Army "Missile Master" sites and related facilities,

in order to provide an advanced warning for the missile batteries.

Having acquired and positively identified a hostile

aircraft, a second radar, the Target Tracking Radar (TTR) would be

aimed at and electronically locked onto it. This radar would then

follow the selected aircraft's every move in spite of any evasive

action taken by its pilot. A third radar, the Missile Tracking Radar

(MTR) was then aimed at and electronically locked onto an individual

Nike missile located at the nearby Launcher Area.

Both the TTR and MTR were linked to a guidance computer

located at the IFC Area. This analog computer continuously compared the

relative positions of both the targeted aircraft and the missile during

its flight and determined the course the missile would have to fly in

order to reach its target. Steering commands were computed and sent

from the ground to the missile during its flight, via the Missile

Tracking Radar. At the moment of closest approach the missile's warhead

would be detonated by a computer generated "burst command" sent from

the ground via the MTR.

For surface-to-surface shots, the coordinates of the target

were dialed into the computer and the height of burst was set by crew

members at the Launcher Area. The standard technique was for the

missile's guidance signal to be terminated as it dove vertically onto

its target. Detonation of the warhead was via the pre-set barometric

fusing. Alternately (and presumably as a back-up system) the warhead

could be exploded via contact fusing when it impacted the selected

target or target area.

End Of The Nike Era

Although Nike was created in response to Russian efforts to

design and deploy long-range bomber aircraft during the early years of

the Cold War, Russian military strategy soon changed. Fearing that

their manned aircraft would be too vulnerable to attack by supersonic

American interceptor aircraft armed with rockets and missiles, the

Russians decided to focus their attention on developing ICBMs --

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles -- against which there existed no

effective defense. As a result, the Russians never deployed a large and

capable strategic bomber force comparable to the Strategic Air Command

of the United States Air Force.

The shifting nature of the Soviet threat meant that the air

defense role, for which Nike was originally intended, became relatively

less critical as time passed. Defense dollars were needed for other

projects (including the development of American ICBMs and potential

missile defenses) and to fund the rapidly growing war in Vietnam.

Accordingly, beginning in the mid 1960s, the total number of

operational Nike bases within the continental U.S. was steadily reduced

on an almost annual basis.

The signing of the SALT I treaty in Moscow during the spring

of 1972 limited the number of missiles with ABM (Anti-Ballistic

Missile) capabilities. Nike Hercules, due to its limited capabilities

against certain types of ballistic missiles, was included in this

treaty. During 1974, all remaining sites within the nationwide Nike air

defense system were inactivated. Army Air Defense Command (ARADCOM)

which administered this system was closed down shortly thereafter. One

of the nation's most significant Cold War air defense programs had come

to an end.

In spite of the termination of the nationwide Nike program,

Nike missiles remained operational at sites in Florida and Alaska for

several more years. Others remained operational with U.S. forces in

Europe and the Pacific, and with the armed forces of many U.S. Allies

overseas. Although no longer in the U.S. inventory, more than four

decades after the first Nike missile became operational in the U.S.,

Nike Hercules missiles are today deployed by the armed forces of U.S.

allies in Europe and Asia, and are likely to remain in service well

beyond the year 2000.

|

| Nike

Missile Specifications & Performance Data Dillsboro UFO Incident Directory NICAP Home Page |